(Super) Model Mania

The addictive culture of the 90s supermodel and the dangers of its return.

Content warning: This article discusses drug use and eating disorders.

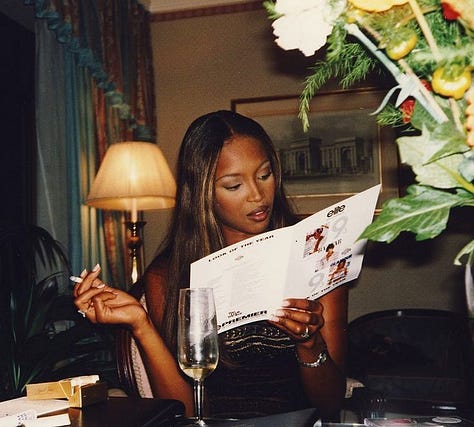

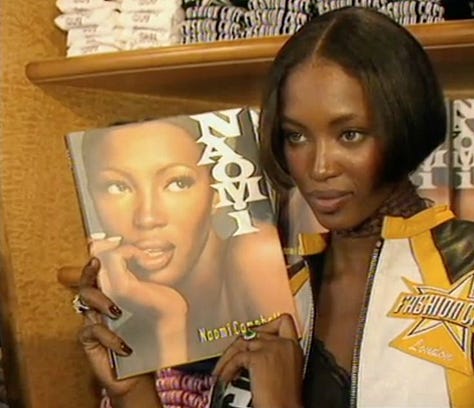

The 80s and 90s saw the birth of a different kind of star than what we were used to: supermodels. The new glamorous faces of fashion with lithe figures and effortless elegance. They had a sense of grandeur that would shape the era: big blowouts, casual glamour, minimal makeup and an effervescent sense of confidence . That's where the “Big 5” supermodels came from; Linda Evangelista, Naomi Campbell, Claudia Schiffer, Cindy Crawford, and Christy Turlington. But soon, an era-defining model would emerge as a sixth fixture among the group: Kate Moss.

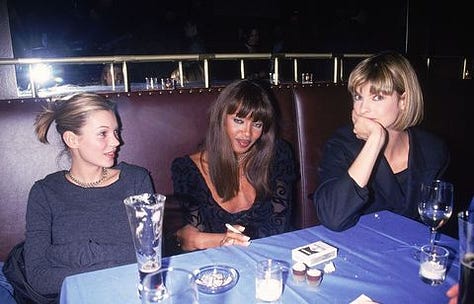

Kate Moss epitomized the 90s 'it girl'—grungy yet fragile, she became a fashion icon whose influence extended beyond the runway. After being discovered at the ripe age of 14 at JFK airport, Moss rose to fame very quickly. She became a tabloid and cultural fixture, not just for her beauty but for her embodiment of the “heroin chic". This term refers to the pale, skinny, and fragile yet grungy look that gained popularity in the mid-90s. The influence of this aesthetic on culture was undeniable, even drawing comments from President Clinton: “You do not need to glamourize addiction to sell clothes. The glorification of heroin is not creative; it’s destructive. It’s not beautiful; it’s ugly. And this is not about art; it’s about life and death. And glorifying death is not good for any society.”

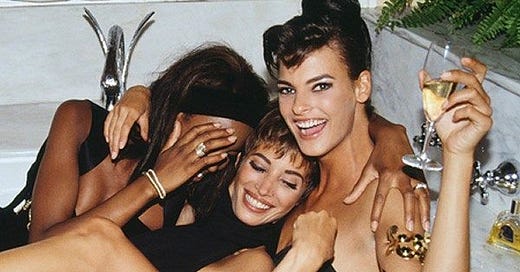

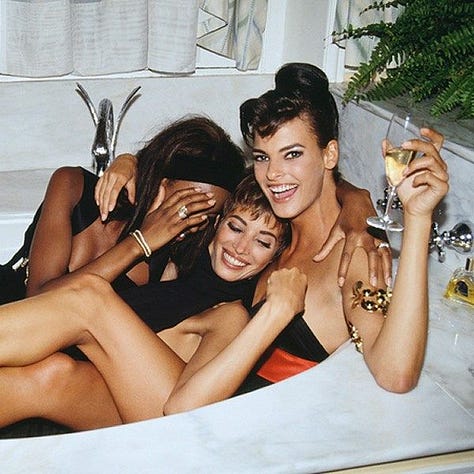

With paparazzi and pop media, our world looked to eliminate all boundaries of privacy and pry into the addictive lifestyles that models like Moss symbolized. Images depicting their boney physique and nearly adolescent qualities and stories about their tantalizing lives would impact the desire of young audiences to look and live like them. The media loved not only to capture their lives as models but as people, blurring the line between art and real life. From the Versace after party to the star studded exclusive New York clubs, the party scene of the 90s became iconic.

But what we often fail to address about this time is that the Supers at their core were young girls under a lot of pressure and power. The waif-like supermodel kitsch extended beyond parties and clothes to a culture of excess that capitalized on drug addictions and eating disorders. Models led messy and complicated lives that were scrutinized under the public eye. Kate Moss especially became a tabloid favorite as they splashed cruel and crude variations of her name in all newspapers. But nonetheless, she’s remained one of the most famed, loved, and envied supermodels in the world.

The feminine ideal has long been influenced by supermodel culture, viewing them as pinnacles of fascination, but the fashion world has been notoriously cruel in its expectations. As Donal MacIntyre investigated and then stated “Some models [would] do lashes of cocaine just to keep the weight off…They [needed] to stay slim and sleek. It is a brutal, brutal trade... Plus, cocaine is a party drug; fashion is a party industry.” Many models, including Gia Carangi, struggled with drug addiction, and some ultimately lost their lives to it. The fashion industry's double standard was clear: models were expected to maintain a certain appearance at any cost but were harshly judged for using drugs.

The world of fashion became riddled with death and it took tragedy to realize such. David Sorrenti, a photographer incredibly influential in establishing the style, died of health complications related to his heroin use, in part, such tragedy is what prompted Clinton’s address. Sorrenti’s photography is undeniably beautiful and captured to detail the urgency and decade of youth culture. The fashion world loved it, yet following his death, it was obliged to acknowledge the darkness that the aesthetic had embraced.

The waif supermodels of the 90s had popularized fashion staples that remain relevant today: the sheer clothing, the slip, the minimal makeup, the ubiquitous little black dress. The notion of the supermodel endures because their images sell. The style of the "off-duty supermodel" is one that has been both copied and coveted through the past years and our media has circled back to the underlying problems of the 90s Supers.

Despite the fact that we have seen an increase in trends encouraging body positivity and inclusivity, the world of fashion and fame has constantly gone back to the thin heroin chic aesthetic. Think of the normalization of weight loss drugs like Ozempic and the revival of icons such as Carrie Bradshaw and Kate Moss. Both quoted to prioritize fashion over their health. As Lauren O’Neil notes “Kim and Khloe Kardashian, once (not unproblematically, of course) seen as emblematic of fashion’s acceptance of a non-size zero body type, have flaunted their new, tiny frames”, with a scandal being involved in Kim’s weight loss to fit into her Marilyn Monroe 2023 MET Gala dress. It's kitsch—excessive, commercial, and nearly vulgar.

The return to the hollow excess of the 90s supermodel grungy kitsch reveals a problem that transcends the period of the 20th or 21st century, “The fashion industry has historically approached the body — particularly the female body — as malleable, something that can be molded and changed with the cut of a garment, sculpting underwear, diet, exercise, and even plastic surgery.”

Famed photographer Corinne Day claimed that in its way the 90s heroin chic was an attempt “[to be] more honest and realistic...an attempt to move on from fashion’s traditional representations of impossible beauty”. But as Maddison Lynne writes, “These photographs only created a new standard of impossible beauty. This standard of beauty praised a bony, anorexic physique and an adolescent body [and]... the images seemed to suggest that using narcotics would produce these bodies”.

It's what my global politics teacher would call a “structural issue”. It's a cultural issue with the representation of women and the expectations that industries have placed upon them- it’s not the supermodel’s fault. In the beginning, they were empowering. Larissa Bills, co-producer of “The Super Models” says, “What I took away from making this series is that beauty and feminism are not mutually exclusive. These women were part of a movement, along with Madonna, that said women could be sexy and wear high heels and lipstick, and yet still be powerful.”

Unlike in the 90s, consumers nowadays are much more aware of the implications of the media that we consume and the nuances of the fashion industry. Plausible deniability is not a card that the fashion world can play anymore and as consumers, we should not allow for it either. The 90s left a lot to be nostalgic about but after all, the trends that it promoted were nothing more than that: trends.

Fashion should be fun, fearless, and fabulous—not fatal. Sheer tops and big blowouts don't need the backdrop of drugs and descent to work. The pursuit of fashion should never demand the suffering and control of female bodies. Instead, fashion should look to celebrate the strength and confidence that the famed supermodels exemplified. What I've always loved most about supermodels is the extent of their confidence and powerful attitude. I’ve always seen them as successful women who were both beautiful and strong. I think that's what ought to be salvaged from supermodel culture, not the fashion world’s obsession with thinness and addiction. Fashion and photography have all the power to be provocative, thought-provoking, and culture-defining. They show a paradigm of style but must refocus how they portray such. After all, true style is about more than just appearance—it's about expressing who you are with nothing but confidence.